Today, if you visit the place where the village of Blazov once stood, you would find it hard to imagine that once more than a thousand people inhabited the area where near where you are standing. Other than a cellar door marking the cellar once owned by the Bajus family and four stone pillars of a barn where the rectory once stood, there is no other evidence of the village’s existence. Even the cemeteries and grave markings of those villagers who once lived and died in the village have been returned to nature; nurturing the meadows and forests that were there before the first settlement. The village has vanished almost without a trace but the memories remain of those who refuse to forget. It is as it was in the beginning, natural and beautiful.

The Area of Blazov.

Until 1918, the village of Blazov belonged to Saris County in the Sabinov District of Austria Hungary. Then in 1918, the villagers found themselves citizens of the newly created country of Czechoslovakia. Today, the village lands are attached to neighboring TichyPotok, a village in the Presov Region of the County of Sabinov located in the Northeastern part of Slovakia. Blazov stood in the northeastern part of the Levoca Hills where the Chmelov, Ciernohuzec, Zamcisko, Kaligura, Ciernahora and Ciernakopa Mountains form the northern ridge of a small valley. The Javorinka Hill massif closes the valley to the south where the Torysa River flows. This is old land. The Torysa River may derive its name from the Celtic “thor iza”, which means mountain water. Local legend holds that an ancient castle stood atop Zamcisko Hill; and a document from 1600 does say, “on the top of the Zamcisko we can see the round, stone watchtower.” In the 13th century, people called the land Seuwold, old German for “pretty woods”. Within the 17,000 acres where Blazov stood, dense forests of fir and deciduous trees grow. The woods give way to mountain meadows. Springs, streams and creeks dot the landscape. Deer, fox and wolves live here, along with many kinds insects, reptiles and birds. There are mushrooms and wildflowers of seemingly endless variety and beauty.

The Origin of the Blazov.

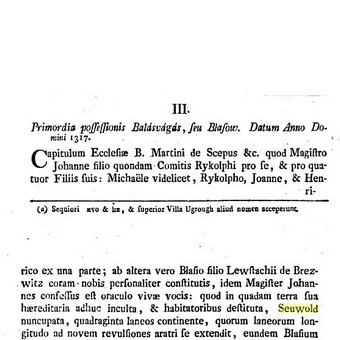

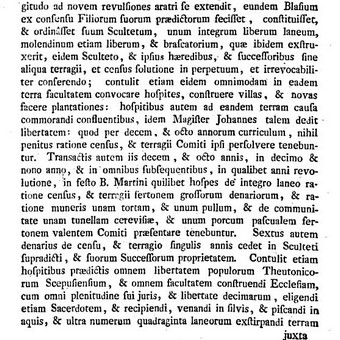

In 1274, lords Kokos and Rikolf of Velka Lomnica received Torysa village and its vicinity in a land exchange with Detrik, leader of the Spis Saxons. Kokos and Rikolf were of German origin, and they chose the settlement of Brezovica near Torysa village as their home. Their descendants would be titled the Berzeviczy de Berzevicze et Kakaslomnitz (Berzeviczy of Brezovica and Velka Lomnica). In the 18th century, the family became simply Berzeviczy. In 1317 in the ecclesiastical town Spisska Kapitula (Spis Canonry), Rikolf's son, John, and John's sons: Michael, Rikolf, John and Henrik, signed a contract with Blazej of Brezovica. The agreement, based on the so-called German law, allowed Blazej to settle a village in an unpopulated area previously called Grunwald. The contract contained the following conditions:

- Settlers may cut 40 parts of the forest, and the forest they clear may be converted to fields.

- Blazej shall hold the hereditary title soltys (village head).

- The soltys may own: one field, a windmill, and a brewery.

- Settlers may build a church without paying tithe and may freely choose a priest.

- Settlers may hunt and fish within the borders of the new village.

- Settlers will be exempt from taxes for next 18 years.

- After 18 years, each settler will pay tax in the form of: 7 denars, 1 bread, 1 chicken, 1 pig,

- - the whole village shall provide 1 barrel of beer.

- The soltys has the right to serve as judge in the village, and to receive from peasants in the village every sixth denar of the paid tax.

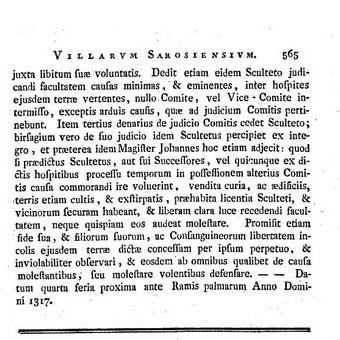

The contract was dated: “Datum IV. feriaproxima ante Ramispalmarum. Anno Domini MCCCXVII”. (4th Friday before Palm Sunday, 1317 = March 19th 1317)

Thus, Blazov, the village named after Blazej, came to be. Called Balázsvágás in Hungarian, the village name means Blazej's Glade. Little is known about Blazej, except that he was the son of Leutasch of Brezovica. However, he may have been one of two servients (military free men in service to the king) described in a document from Spis Canonry. In the year 1270, Princess Kunigunda awarded lands in Pokoj village to servients Blazej and Marcel. A Dispute over Marcel's land caused him to leave Pokoj and move to the Upper Torysa. Likewise, Blazej sold his land in Pokoj in 1286. Perhaps he followed Marcel to the Upper Torysa and became the Blazej of Blazej's Glade.

How people lived in the village and its settlements.

In 1427, a Berzeviczy family inventory described the village of Blazov. The village contained just six houses. The agricultural customs of the original Slovak and German settlers did not suit the terrain, and Blazov failed to grow. Incursions by the Polish army into north-eastern Slovakia in the 1470s and 1490s also contributed to decline. The arrival of Wallachs (Ruthenians) repopulated the and. Evidence for their existence appears in court records. In 1480, an investigative document from Saris County described an attack by Wallachs from Blazov against Nicholas from Brezovica. Nicholas had been traveling from Zilina town with a wagon load of clothes and fabric. Stanislav from Brezovica, the landowner (landlord) at that time attacked and killed a Wallachian living in Tichy Potok while he was on the road near Blazov.

Another legal document from 1513 confirms the presence Wallachs in Blazov. Peter of Spis Hrhov, landlord of the village Nizne Repase, charged in Spis County court that serfs of Francis of Brezovica had illegally grazed their sheep in the meadows of Nizne Repase. When Peter seized the sheep, armed Wallachs from Blazov and their landlord burst into Nizne Repase. They reclaimed their sheep, took some cattle, and wounded one villager.

Landowners invited robust Wallachs from Galicia and Ruthenia to settle in the area that is now northern Slovakia. They signed agreements according to Wallachian law setting out the privileges and conditions for the new-comers. The law required Ruthenians to guard the borders of the kingdom in the Carpathians, and to ensure the protection of roads. In exchange, the Ruthenians received free use of royal pastures and forests. After ten to twenty years of tax freedom, but an obligation to pay tax of one-twentieth cattle, wool and cheese.

Wallachian dukes possessed powers similar to those of the old soltys, although they were elected to the title by their fellow Wallachs. The duke represented the village in negotiations with the authorities, collected taxes for the suzerain, supervised tending of the forest, and determined how many sheep would graze on which javorina. (a javorina is a meadow suitable for grazing sheep.) The Wallachs kept these privileges until the Urbarial reforms of Maria Theresa in 1773. Blazov and its surroundings suited the Wallachian lifestyle. The villagers grazed sheep on the slopes Javorinka Hill. They turned gentle slopes north of the village into fields for farming. On the steeper slopes, they grew meadows of hay for cattle.

The village thrived and became one of the largest villages in the area. Blazov received royal privileges allocated to significant villages. Beginning in the 18th century, Blazov had the right to hold two markets a year. Also on the 18th century, Blazov received a royal forge for the smelting of iron ore and iron working. Blazov also had the privilege to produce charcoal, a by-product of wood shingles and other wood products made in the village. The residents of Blazov were mostly Ruthenians, but there were also descendants of the original Slovaks, Germans and others who had migrated to the area over the years.

Some residents already had surnames in the 18th century, such as Fenda, Gargala, Gradzilla, Garnek, Pacinda, and Sweda. Even so, many villagers are remembered in church records only as: Andrij from the slope, Jurko from the garden, or Misko from the bridge, and so on. Surnames in Blazov didn't stabilize until the second half of the 19th century. Church records from 1818 refer to one Blazov man as "Jurko from Zagorodka". In 1830, his name is written as "Georgius Havrilovitz". In 1845 he becomes "Georgius Havrilyak alias Bajusz". In 1860, finally, he is “Georgius Bajusz”. Interestingly, church records indicate that one resident, Nicholas Krajnyak (1766 – 1870) lived to be 104 years old. The oldest age recorded of any person who lived in Blazov.

During the existence of the village, its inhabitants were affected by several disasters. They were epidemics of plague and cholera. People survived the famine in the middle of the 19th century. Devastating storms and the flooded Torysa river often destroyed crops and houses, killing animals and people. Large fires in the village were not uncommon. The inhabitants survived all these insults and never thought that one day they would have to leave the village forever. But it happened in 1952 by order of the communist government.

The settlement was founded as a base for the hunting lodge. There were two mills, one sawmill, and in the mid 18th century, the royal forge was built there. The population consisted of skilled laborers invited by the nobles of Brezovica to manage the forest, process timber, iron works and fill related jobs. Most members of the settlement were Roman Catholic. A Jewish community also settled there, and in 1898 it numbered 23 people. Gypsies lived in houses along the river between the Berzeviczy hunting lodge and Dolina. The last inhabitant was Anna Garancsovsky, born 1897, who died in 1955 . She was the last villager to die in Blazov.

The German names Zoller, Zonger and Roth appear in the church records as living in Zdiar. These German, Roman Catholic families maintained lasting relationships with other German families in eastern Slovakia, as evidenced by two residents of the town Stos who died in Zdiar during the cholera epidemic of 1831.

All that is known of this village is from the Berzevicy family property inventory of 1427. The inventory states, “the settlement Laszinóvágása (also known as Lazyouagasa) is located on the border area between villages Blazov and Bajerovce.” The settlement later disappeared.

The Ludrovec Grange is first mentioned as a seperate farmstead in 1851 (At that time as Rudlovec). Seven people lived there at that time. The grange sat at the lower end of Blazov, under the Cierna Hora mountain. The owner was the Dzug family from Brezovica.

Religion of the village.

Wallachian immigrants brought with them the Byzantine rite of the Catholic church in which the language of the liturgy is old church Slavonic. Wallachians were free to choose their priest or "batko". The priest could be married and have a family, but he did not always have the privileges accorded Roman Catholic priests. He could not require tithes, and he held a position similar to other serfs. Ruthenian priests never held major assets, as can be seen in the record of a 1750 ecclesiastical visitation to Blazov. The record describes the pastor's property, his annual income, and expenditure. The record notes that the priest holds only basic ceremonial clothes and simple liturgical objects, of which the gold-plated, silver chalice is most precious. While the church is constructed from stone and in good condition, the record says that the pastor lives in a ruined, ancestral cottage near a small garden. The record includes a price list of religious services:

Baptism - 90 dimes

Marriage - 1 Denar

The larger funeral - 1 Denar

The smaller funeral - 72 dimes

Blessing of a house - 60 dimes

In 1915, agitators traveled through the villages of the Upper Torysa trying to convince Greek Catholic believers to convert to the Orthodox faith. The agitators were mostly emigrants returned from America. They argued that the Greek Catholic Church was weak and virtually unknown in the United States. Their efforts to convert were unsuccessful, partly due to the activities of pastor Emanuel Mankovich. In 1950, the communist government of Czechoslovakia banned the Greek Catholic Church, and gave all of Greek Catholic Church assets to the Russian Orthodox Church. Greek Catholics, including villagers from Blazov, fought the ban, and they regained the Greek Catholic Church in 1968. One of the main Greek Catholic champions, along with Bishop Gojdic, was Bishop Hopko, who grew up in Blazov from the age of seven with his uncle Demeter Petrenko.

Known pastors in Blazov:

1330 Nicholas

1726 - 1735 Basilius

1735 - 1737 Anton Jaromis

1737 - 1757 John Mankovic

1757 - 1757 George Tarasovic

1757 - 1791 Michael Mankovic

1796 - 1852 Andrew Mankovic

1852 - 1863 Andrew Samovolsky

1863 - 1892 Anton Rojkovic

1892 - 1924 Emanuel Mankovic

1924 - 1940 Demeter Petrenko

1940 - 1948 Nicholas Rojkovic

The School

From 1921 to 1945, the school was known as the Blazov Greek Catholic Grammar School.

From 1945 to 1949, it became the State Grammar School.

From 1949 to 1953 it was the National School.

n 1950, a Ukranian language, lower, secondary school was established.

The schools spanned grades 1 through 9 in four classes of 35 to 40 students each.

Known teachers: 1843 - ? Ladislav Krafcik, 1857 - 1867 Michal Krafcík, 1838 - 1872 Alexander Ilykovich, 1873 - 1897 Peter Keselak, 1876 - ? John Kopcak, 1898 - ? Joseph Stulakovic, 1903 – Theodorus Jobbágy, 1908 - Ján Magyar, Margaretha Tátrai, 1931 – Adalbertus Silla, 1942 - 1953 Peter Macek

Emigration

These first wave emigrants from Blazov headed mainly to Farrell, Sharon and Sharpsville in Pennsylvania, and to the Youngstown area in Ohio. A second wave of emigration began around 1920 when the American-born children of returnees reached adulthood. These children exercised their right to U. S. citizenship, and headed for Cleveland, Pittsburgh, and California.

A third wave left Blazov in 1946. They moved to the Czech Republic where the government offered property abandoned by the Sudetenland Germans. The fourth and final wave of emigration was in 1947 when about 70 people emigrated from Blazov to the USSR. It was based on an agreement between Czechoslovakia and the USSR about the return of the Czechs from the Volyn area in Transcarpathian Ukraine and the voluntary eviction of Russians and Ruthenians living in Czechoslovakia to Volyn. At that time, 33,000 Czechs returned to Czechoslovakia, however Russians and Ruthenians weren't interested in moving to the USSR. Communist agitators visited Ruthenian villages and promised large, fertile fields and nice homes in the Ukraine and about 12,000 Ruthenians believed the propaganda and left for Volyn only to find the promises nothing but lies as they found themselves with nothing, losing even their Czechoslovak citizenship, and being told any attempt to their return was illegal. Finally after years of pleadings, Nikita Khrushchev made a determination to allow their return to their village and about 70 percent of those who had a chance to return, did so, but by that time the village no longer existed.

Forced Evictions – The end of Blazov.

Building Javornia meant more than creating a military base. It meant suppression. The ruling communists regarded the people of Blazov as rebels. The majority of villagers had been against the ongoing collectivisation of agriculture. Successful farmers in Blazov held a strong influence, and they were joined by new landowners who had made money in America and bought land here. Although most people in the village disagreed with the eviction, and were unimpressed by the compensation provided, evictions began on May 30, 1952. The first to be thrown out were the residents of Certez. They resisted and the police were called. Dolina was next to be evicted, and finally the entire village of Blazov. Villagers were resettled to Sarisské Michalany, Zakovce, Sabinov, Huncovce, Sobrance, Snina and SpisskePodhradie. However, some returned home. In 1953, a handful of brave Blazov villagers reclaimed their former homes. More villagers returned until the government took action. People were forcibly removed, and their houses destroyed. There would be no place left to return. The last villager left Blazov on May 26, 1955. Now majority of people were moved to the village Zakovce, on the foot of the Hight Tatras Mountains, where they built their new houses. In 1954, four men who opposed the forced evictions were arrested and convicted. Each received suspended sentences from between 1 month to 1 year. They were: Juraj Valko, Mikulas Parimucha, Juraj Kol, Jan Kravec and Michal Sekerak. After 1955 only the Blazov church and a few barns remained standing. . The church was demolished later to prevent it becoming a shrine and/or a pilgrimage destination. On December 1, 2010, the Slovak government passed Regulation No. 455/2010) and officially abolished the Military Area whose creation forced the eviction of Blazov. The land is now attached to the village of Tichy Potok.

Language correction: Dave Duricy & Jan Bayus